World Health Day 2022

THR: A Historic Opportunity for Our Health & Our Planet

World Health Day is celebrated annually on 7 March, which was the founding date of the World Health Organisation (WHO) in 1948. Each year focuses on a specific health topic of concern to people all over the world. This year, global attention will be directed towards ‘our planet, our health’(1); “Are we able to reimagine a world where (…) economies are focused on health and well-being? Where cities are liveable and people have control over their health and the health of the planet?”(1). Amongst an extensive agenda of health concerns, the human and environmental harms of smoking will be a particular focus for the partnered WHO and United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)(2). This article will provide commentary on the partnership’s efforts, with reference to the historic opportunity tobacco harm reduction (THR) has to improve our people’s health, and our planet’s:

1. Cleaner, Safer Alternatives to Combustion

2. RESET: Environmental Considerations of E-Waste

3. A Harm-Reduced Future

1. Cleaner, Safer Alternatives to Combustion

Consider the parallels between harms from air pollution and smoking. Firstly, from a human perspective, as the world gets more populated, there is a concomitant rise in the need for fuel for energy used in transport, cooking, heating and electricity. With over half the world not having access to clean fuels or technologies, the air we breathe is becoming harmfully polluted: nine out of ten people worldwide breathe polluted air(3). It is estimated by the WHO that there are 7 million premature deaths secondary to air pollution, 4 million of which are from indoor air pollution (e.g., from stoves or lamps). Tragically, 91% of these premature deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)(4). Air pollution has become a critical risk factor for non-communicable disease (NCDs), being implicated in 24% of all adult deaths from cardiovascular disease, 25% from stroke, 43% from COPD, and 29% from lung cancer(3).

Similarly, smokers inhale 7000 chemicals from cigarettes, 70 of which are known to be carcinogenic(5). Over 80% of smokers live in LMICs(6); just like with air pollution, it is the poor, vulnerable, and marginalised population groups that suffer most(7). Annually, there are over 8 million premature deaths attributable to smoking(8).

What do smoking and air pollution have in common? Combustion. Humankind’s first interaction with fire is estimated to be about 1.5 million years ago in Africa. We began to wield and control fire more regularly about 7000 years ago(9), incidentally around the same time Native Americans first started cultivating tobacco(10). But it was the discovery of fossil fuels during the Industrial Revolution that catalysed our use of combustion(11). Coal, oil, and gas became indispensable ingredients to economic and technological progress, and they continue to currently supply about 80% of the world’s energy(12).

Unfortunately, the combustion of fossil fuels has also had major, harmful implications for our planet and our health(11). In addition to the aforementioned 7 million premature deaths due to air pollution, atmospheric concentrations of CO2 have risen by 50% since 1750 – higher than they have ever been, and more than what happened naturally over a 20,000-year period(13). Over 97% of actively publishing climate scientists agree that climate-warming trends are extremely likely due to human activities(14). This is manifesting as rising sea levels, shrinking ice caps, ocean acidification, increased droughts and heat waves, and more regular extreme weather events(15).

With regards to smoking, its harmful effects were formally recognised as early as 1604, when King James I of Great Britain issued a treatise ‘A Counterblast to Tobacco’. In this treatise, the King lamented numerous social and health problems associated with smoking, and even instituted a 4,000% tax hike on tobacco(16). Nowadays, smoking is incontrovertibly recognised as the biggest single cause of noncommunicable disease deaths in the world. If current trends persist, another billion tobacco-related deaths will occur in the 21st century(8).

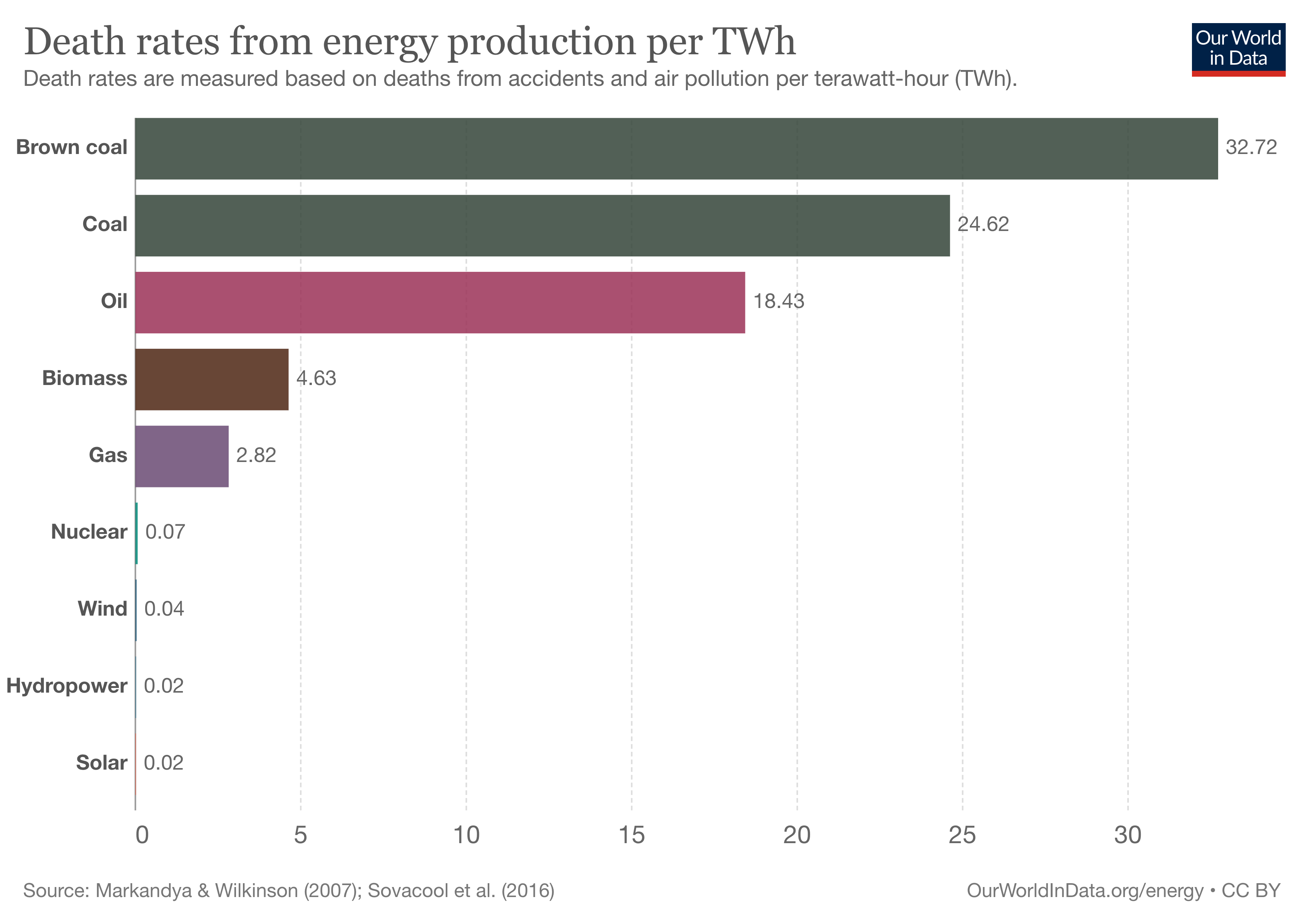

However, it does not need to be this way, because cleaner and safer alternatives have been found for both fossil fuels and smoking. With the advent of modern renewables - such as solar, wind and hydropower – as well as nuclear energy, the world is gradually decarbonising its energy sources. With the obvious benefits of reduced carbon emissions for our planet, the harm-reduction potential from a human perspective is also staggering. According to Our World in Data, the death rates from energy production (per terawatt-hour) in solar, hydropower, wind, and nuclear power are all at least 97% lower than in fossil fuels(17):

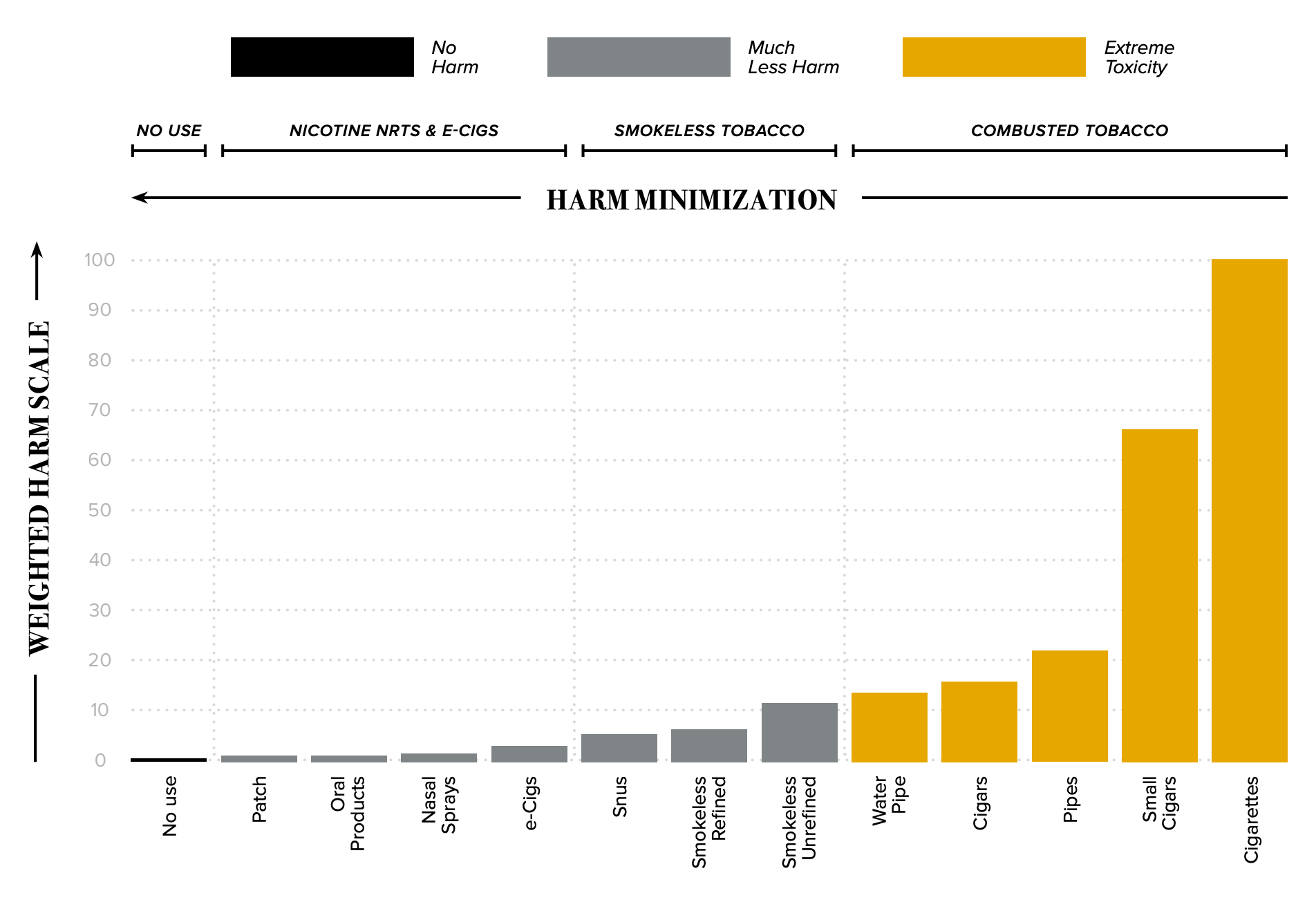

Correspondingly, the advent of non-combustible, safer nicotine alternatives to smoking is a historic opportunity to save millions of lives. It has long been understood that people smoke for the nicotine but die from the tar(8). The innovation of THR products has paved the way for nicotine to be delivered to the consumer without the tar. There is no evidence that nicotine causes cancer, lung disease, or heart disease(8). As with climate change, there is independent and global consensus that THR products are significantly safer than combustible cigarettes(18). Review the graph above indicating death rates from energy production, and consider the parallels with the findings from Nutt et al regarding the harm continuum below(18). THR products (e.g., e-cigarettes and oral nicotine) are analogous to modern renewables (e.g., solar and wind power) in terms of their 95% harm reduction potential in comparison to their combustible, carbon alternatives:

The THR harm continuum - adapted with permission from Nutt et al(18)

2. RESET: Environmental Considerations of E-Waste

Cigarette butts are the most abundant form of plastic pollution in the world. 5.6 trillion cigarettes are smoked annually, two thirds of which are improperly disposed of. This manifests as 766.6 million kilograms of toxic trash every year; it is the commonest plastic litter found in beach clean-ups(19). The environmental harms are clear – microplastic leakages damage marine ecosystems considerably. With the accumulation of microplastics in the food web, there are also potential harms to human health(20).

The WHO and UNEP have partnered this year as part of the Clean Seas Campaign – a global coalition comprised of 63 countries dedicated to tackling the issue of marine plastic pollution(19). As part of the campaign, the WHO FCTC produced a video about the environmental impact of cigarettes on the environment. Apart from the uncalled for and unscientific demonisation of nicotine, the video is a worthy call to action in reducing environmental harms of cigarettes(21).

So, what role does THR have in addressing this issue? Firstly, it is important to be forthright about the uncomfortable truth that THR products do not have a clean record when it comes to waste disposal(22). In the lifecycle of an e-cigarette’s production, use, and disposal, there are numerous chances for waste mismanagement. Improperly disposed e-cigarettes present biohazard risks in the form of leakage of highly concentrated nicotine, lithium-ion batteries, microplastics, and heavy metals (e.g., mercury, lead, bromine)(22). E-waste in general is already an overwhelming problem, with the unfavourable outcome of many Western countries shipping their E-waste to developing countries(22). The problem is compounded by the existence of disposable e-cigarettes; in 2015, 19.2 million of the 58 million (a third) e-cigarettes and refills in the United States were single-use(23).

How can these risks be mitigated? The good news is that with responsible management – recycling, disassembly, and disposal – used, non-tampered e-cigarettes are not classed as hazardous waste. However, in the unused form, e-cigarettes containing nicotine liquid would still be listed as hazardous waste, and should be managed accordingly by waste specialists(22,24).

From regulatory and industrial perspectives, there is an urgent need to enact mechanisms to reduce the potential environmental harms from e-cigarettes. At a German academic conference in December 2021, Professor Heino Stöver proposed a new regulatory framework for nicotine vaping products called ‘RESET’. The second E in the acronym stands for Environmental considerations, and the following solutions were proposed: • The use of recycled material should be encouraged in manufacturing of the THR products and their packaging • Take-back schemes should be mandated for both pods and devices • At the end of their lifecycle, responsible recycling and disposal by consumers should be incentivised through end-of-life buyback programs, and easy access to recycling centres. • Manufacturers should be penalised if they do not provide proper collection and recycling solutions

The extended producer responsibility contained within the above propositions was emphasised by Dr Delon Human, CEO of the Africa Harm Reduction Alliance, at a conference in Nairobi in February 2022: “If manufacturers put rubbish in their products, they must be held accountable”. Similarly, if manufacturers’ products are piling into mountains of mismanaged waste, they should also be held accountable. This must not, however, negate consumers’ equal responsibility in managing their own waste responsibly, as stated by Gregory Conley, President of the American Vaping Association(25).

3. A Harm-Reduced Future

The road to a healthier future for our people and our planet must be paved by three elements: compassion, collaboration, and pragmatism. At the heart of harm reduction is the acceptance that whilst no human activity is free of risk, the compassionate way forward is to minimise any potential harm from said activity. This is particularly important considering that the combustion of tobacco and fossil fuels is laced with disproportionately greater harms for poorer and marginalised population groups(7). To reiterate, over 80% of the world’s smokers live in LMICs(6), and 91% of premature deaths due to air pollution occur in LMICs(4).

Expecting the sale of cigarettes to be halted immediately is as ideologically utopian as expecting all fossil fuel-derived energy to be halted immediately. One cannot just pull the rug from under these multi-billion-dollar industries and supply chains without incurring catastrophic economic damage and a surge in illicit trade, and therefore exacerbation of health and wealth inequalities(26,27).

Working towards solutions will be a complex and iterative process, requiring multi-sector collaboration. In practical terms, this looks like the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change’s COP26 meeting, which invited varying perspectives to participate in the marketplace of ideas, including representatives from the fossil fuel industry. Sadly, the WHO FCTC’s ongoing exclusionary approach is just yielding a closed bubble of cultivated groupthink in its COP meetings(28). It is particularly lamentable that the very people affected by COP9 decisions, the International Network of Nicotine Consumer Organisations (INNCO), are denied even observer status(29).

We should be striving for consumer representation and industry transformation, based on science rather than ideology(30). Rather than demonising and excommunicating businesses and consumers for their (legal) supply and use of harmful nicotine/energy sources, they should be involved in the rehabilitative process of pursuing safer alternatives in the interest of our collective health, and our planet.

References

- World Health Organization. World Health Day 2022: Our planet, our health [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://www.who.int/campaigns/world-health-day/2022

- UN Environment Programme, WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. UNEP, Secretariat of the WHO FCTC partner to combat microplastics in cigarettes [Internet]. Newsroom. 2022 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://fctc.who.int/newsroom/news/item/01-02-2022-unep-secretariat-of-the-who-fctc-partner-to-combat-microplastics-in-cigarettes

- World Health Organization. 9 out of 10 people worldwide breathe polluted air, but more countries are taking action [Internet]. News. 2018 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/02-05-2018-9-out-of-10-people-worldwide-breathe-polluted-air-but-more-countries-are-taking-action

- World Health Organization. 10 Things To Know About Air Pollution [Internet]. Newsroom. 2022 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/how-air-pollution-is-destroying-our-health/10-things-to-know-about-air-pollution

- NIH National Cancer Institute. What harmful chemicals does tobacco smoke contain? [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/tobacco/cessation-fact-sheet

- World Health Organisation. Fact Sheet: Tobacco [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Dec 6]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco

- Africa Harm Reduction Alliance. Dear WHO | STOP killing smokers by protecting cigarettes from healthy competition [Internet]. YouTube. 2021 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gvhmic3igpE&t=45s

- tobaccoharmreduction.net. An Advocate’s Guide to Tobacco Harm Reduction [Internet]. 1st ed. thr.net; 2021 [cited 2022 Mar 31]. Available from: https://media.thr.net/strapi/d5b691d7b57a532da30f41f52dd63dcc.pdf

- When Did We Discover Fire? Here’s What Experts Actually Know | Time [Internet]. TIME Magazine. 2018 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://time.com/5295907/discover-fire/

-

Tobacco-Free Life. History of Tobacco in the World — Tobacco Timeline [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://tobaccofreelife.org/tobacco/tobacco-history/ -

Ritchie H, Roser M. Fossil Fuels - Our World in Data [Internet]. Our World in Data. 2022 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/fossil-fuels -

Environmental and Energy Study Institute. Fossil Fuels | EESI [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://www.eesi.org/topics/fossil-fuels/description -

NASA. Carbon Dioxide | Vital Signs – Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet [Internet]. Vital Signs of the Planet. 2022 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/carbon-dioxide/ -

NASA. Scientific Consensus | Facts – Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet [Internet]. Vital Signs of the Planet. 2022 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://climate.nasa.gov/scientific-consensus/ -

NASA. Evidence | Facts – Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet [Internet]. Vital Signs of the Planet. 2022 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://climate.nasa.gov/evidence/ -

Document Bank of Virginia. King James I, A Counterblast to Tobacco, 1604 [Internet]. Library of Virginia. 104AD [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://edu.lva.virginia.gov/dbva/items/show/124 -

Ritchie H, Roser M. Nuclear energy and renewables are far, far safer than fossil fuels [Internet]. Our World in Data. 2022 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/nuclear-energy#nuclear-energy-and-renewables-are-far-far-safer-than-fossil-fuels -

Nutt DJ, Phillips LD, Balfour D, Curran HV, Dockrell M, Foulds J, et al. Estimating the harms of nicotine-containing products using the MCDA approach. Eur Addict Res [Internet]. 2014 Apr 16 [cited 2021 Nov 17];20(5):218–25. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24714502/ -

UN Environment Programme, WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. UNEP, Secretariat of the WHO FCTC partner to combat microplastics in cigarettes [Internet]. Newsroom. 2022 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://fctc.who.int/newsroom/news/item/01-02-2022-unep-secretariat-of-the-who-fctc-partner-to-combat-microplastics-in-cigarettes -

International Union for Conservation of Nature. Over 200,000 tonnes of plastic leaking into the Mediterranean each year – IUCN report [Internet]. IUCN. 2020 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://www.iucn.org/news/marine-and-polar/202010/over-200000-tonnes-plastic-leaking-mediterranean-each-year-iucn-report -

WHO FCTC Secretariat. Tobacco has a negative impact on the environment [Internet]. YouTube. 2022 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A_JVz02PwAI -

Hendlin YH. Alert: Public Health Implications of Electronic Cigarette Waste. American Journal of Public Health [Internet]. 2018 Nov 1 [cited 2022 Apr 7];108(11):1489. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6187764/ -

Marynak KL, Gammon DG, Rogers T, Coats EM, Singh T, King BA. Sales of Nicotine-Containing Electronic Cigarette Products: United States, 2015. Am J Public Health [Internet]. 2017 May 1 [cited 2022 Apr 7];107(5):702–5. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28323467/ -

Krause MJ, Townsend TG. Hazardous waste status of discarded electronic cigarettes. Waste Manag [Internet]. 2015 May 1 [cited 2022 Apr 7];39:57–62. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25746178/ -

Clement D, Ossowski Y, Landl M. Why Vape Flavors Matter [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Dec 8]. Available from: https://241yjo5ffc43s84vz4462arn-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/WHY-VAPE-FLAVORS-MATTER-POLICY-PAPER.pdf -

Cotterill J. Illicit trade thrives as South Africa bans alcohol and tobacco sales [Internet]. Financial Times. 2021 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/b9ba721e-cb82-4cb6-9009-58649b04ee4b -

Bates C. The WHO tobacco control treaty meetings are closed bubbles of cultivated groupthink – a comparison with the UN climate change treaty [Internet]. The Counterfactual. 2021 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://clivebates.com/the-who-tobacco-control-treaty-meetings-are-closed-bubbles-of-cultivated-groupthink-a-comparison-with-the-un-climate-change-treaty/ -

International Network of Nicotine Consumer Organisations (INNCO). Bloomberg, the World Health Organisation & the Vaping Misinfodemic [Internet]. 2021 Nov [cited 2021 Nov 17]. Available from: https://innco.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Innco-Dossier-Final-1.pdf -

Antin TMJ, Hunt G, Annechino R. Tobacco Harm Reduction as a Path to Restore Trust in Tobacco Control. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Jun 1 [cited 2022 Apr 7];18(11). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34067476/